North Fork History Project: Shelter Island’s place in Quaker history

It was 38 minutes into the one-hour Quaker meeting before anyone said a word.

Gathered on the grounds of Sylvester Manor, seated in a wooded glade on a jumble of rough-hewn logs fashioned into long benches, there were six at the meeting, seven if you count the small white dog on Shelter Islander Jim Pugh’s lap. They sat largely in silence, until Mr. Pugh gathered the group of Friends together in a circle of hands and called the rise of meeting.

In a time when listening is out, venting is in and most of your friends are people you never actually see, the Quaker approach to worship is distinct, even a bit strange. It must have seemed as strange in the 17th century, to the Puritans of colonial New England, and is one reason Shelter Island’s Quaker history, which goes back to the founding of Sylvester Manor in 1652, is relevant today.

Quaker practices include plain speech, modesty, avoiding showy things such as flags and grave markers and an unwillingness to swear an oath. Activists for peace and social justice, Quakers have advocated for women’s rights and the abolition of slavery.

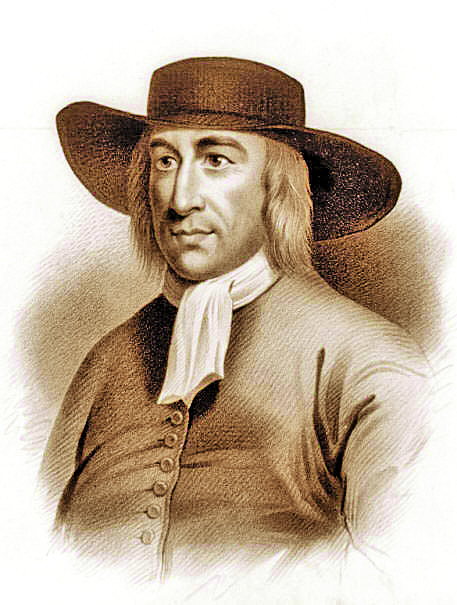

The Religious Society of Friends, known as Quakers, was established by George Fox in England in the mid-17th century, around the same time Nathaniel Sylvester and Grizzell Brinley married in England and crossed the Atlantic Ocean to become the first European residents of Shelter Island.

The Sylvesters brought Quaker practices and beliefs with them. When the passage of anti-Quaker laws in 1656 imposed punishments such as branding, ear-cropping, imprisonment and later banishment and death, Nathaniel and Grizzell Sylvester made Shelter Island a refuge for persecuted Quakers.

The best known of these was the Quaker martyr Mary Dyer, who left her husband and six children in Boston in the early 1650s; moved to England, where she became a Friend; and returned to Boston as a Quaker preacher in 1657 only to be arrested and banished on pain of death.

Despite her banishment, Ms. Dyer went back to Boston and was sentenced to death, but was spared at the last moment. In a bizarre public execution, during which two fellow Quakers were hanged before her, Mary Dyer was made to stand hooded on the gallows, and then suddenly spared. She then made her way to Shelter Island, where she spent the winter of 1659-60, a time historian Mac Griswold describes in “The Manor,” her history of Sylvester Manor, as “the happiest, most dedicated, least fractured time of her life. Her actions embodied her faith; all the rest of life’s concerns had burned away.”

But Ms. Dyer chose once again to return to Boston — and her fate. She was publicly executed in June 1660.

Nathaniel and Grizzell Sylvester also harbored Lawrence and Cassandra Sethwick, Quakers from Salem, Mass., after they were banished and two of their children were ordered sold into slavery. The Sethwicks fled across Long Island Sound to Shelter Island. Physically and emotionally shattered, they both died about a month after their arrival. A copy of Lawrence Sethwick’s last will and testament, written on Shelter Island and witnessed by Nathaniel Sylvester, is dated May 1659.

In 1661, King Charles II issued a royal order meant to stop the executions of Quakers in Massachusetts. It was personally delivered to John Endicott, governor of Massachusetts, by a London Quaker and ship captain named Ralph Goldsmith, who later settled in Southold.

Nathaniel Sylvester’s brother Giles, who was living in London, signed the petition listing the sufferings of American Friends, which prompted the royal order. Historians have posited a link between Grizzell Sylvester’s correspondence with her father, Thomas Brinley, who was in the court of King Charles, and the order to stop the executions of Massachusetts Quakers.

As joyful as the Sylvesters must have been to see the end of Quaker executions, the arrival of Friends’ founder George Fox on Shelter Island 10 years later was likely even more satisfying, as an indication of their prominent position. Mr. Fox had left England for a tour of America in 1671 and, after two months in Rhode Island, finally visited the island in August 1672. He wrote of preaching to hundreds of Native Americans from the porch of the Manor House and of trying to persuade slaveholders in America, such as Nathaniel Sylvester, to free the people they held in bondage. At the time, about 70 percent of American Quakers also owned slaves.

Nathaniel Sylvester died June 13, 1680, at age 70. Grizzell, in settling the estate, followed Quaker practice by declining to swear, “being a person that cannot take an oath for conscience sake,” and instead testified to the inventory of her husband’s estate, which included 23 enslaved people.

Grizzell died June 13, 1687 at 52. In keeping with Quaker practice, the Sylvesters’ graves bore no markers of any kind.

For most of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th, the eighth, ninth and tenth owners of Sylvester Manor were members of the Horsford family. They spent summers at the Manor, and lived in Cambridge, Mass. Eager to recognize the history of the Friends and the Manor’s role as a refuge and haven, the Horsfords dedicated a monument July 25, 1884, to their Sylvester forebears.

They made sure it would be noticed and remembered. A large crowd, including most of Shelter Island as well as friends and colleagues from Cambridge, attended. A three-piece band and a choir performed. The poet John Greenleaf Whittier, known for his dramatic poems about Quaker history, and a friend of Prof. Eben Horsford, wrote a special ode for the event about the Friends’ ordeal and island sanctuary. It included the lines: “A peaceful deathbed and a quiet grave/Where ocean walled, and wiser than his age,/ the Lord of Shelter scorned the bigot’s rage.”

In 1952, Andy Fiske, 13th owner of the Manor and a direct Sylvester descendant, called on Henry Cadbury, who had recently accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the American Friends Service Committee, to conduct a Quaker meeting on Shelter Island. Mr. Cadbury not only came and conducted the meeting, but established a Shelter Island Friends meeting that is still active, albeit with occasional fits and starts. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Friends met at the Garr estate; during the 1960s, at Union Chapel in the Heights; and, starting in 1970, outdoor meetings took place in the grove by the Quaker cemetery at Sylvester Manor.

And that is where six people sat last Sunday, with Friends past and present, in silent awe of all that was around them, and in search of all that is within.

Photo caption: A sign directs visitors to the Friends Meeting area on Shelter Island. (Charity Robey photo)