A look back at the Shoreham nuclear plant protest, 40 years later

Seven years before the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant disaster — which has been chronicled in a new HBO miniseries that concludes tonight — protestors filled Shoreham beach to rally against a nuclear power plant.

The events that day in 1979 ultimately helped stop the power plant from ever becoming fully operational, giving residents peace of mind that they would never be subject to the type of catastrophe that would occur seven years later in the Soviet Ukraine.

The story below was originally published in June 2009 on the 30-year anniversary of the protest.

Despite the heavy rain on a June Sunday, they came by the thousands.

They filled the Shoreham beach with their umbrellas and signs, their buses and cars parked along the roads, their message clear: No nuclear power plant in Shoreham.

Now, 30 years later, the empty power plant sits silent, casting steep shadows from its teal concrete shell. It’s a structure that has had a long-lasting impact on both the Shoreham and greater Long Island community, a building that tells the story of both failure and success.

The protest of June 3, 1979, was a turning point for the fate of the power plant, many say.

“The rally helped to fortify people and helped them to believe that this fight was worth taking on,” said Nora Bredes, who attended the demonstration and went on to lead the Shoreham Opponents Coalition for 10 years and would go on to serve in the Suffolk County Legislature for six years.

It was a catalyst for future events that ultimately led to stopping the power plant from becoming fully operational, she said.

More than 15,000 people turned out for the rally on the nearby Brookhaven Town beach despite the pouring rain, said Ms. Bredes. She marks her involvement against the plant from that day.

A Huntington native and graduate student at Columbia University, Ms. Bredes helped to organize a bus full of people from Huntington to attend the protest.

“There were all kinds of people there,” she said. “As we drove out on the Long Island Expressway from Huntington, we passed bus after bus after bus. We knew it was going to be much bigger than anyone had anticipated, and it was incredibly exciting to know that that could happen on Long Island, that so many people could be engaged and activated.”

In spite of the rain, Ms. Bredes said, people from all different walks of life turned out for the demonstration, including college students, families with little children, older people, homeowners and religious leaders.

“It was uplifting, and very wet,” she said, “But people weren’t discouraged by [the rain].” Greenport resident Jill Ward also attended the rally and remembers the excitement of the crowd.

“There was a certain euphoria about the success of that demonstration,” she said. Ms. Ward, who at the time was a resident of the West Village in New York renting a summer cottage near Orient Point, was one of the more than 600 protesters to scale the fence of the Long Island Lighting Company property and be arrested.

She remembers trudging through the rain, the mud and the underbrush to scale the fence and being peacefully arrested, lying down on the ground and having her hands tied behind her back with plastic cuffs, then being loaded onto the bus to be booked by the police.

“When we were driving away on the bus we were loaded on, we were driving past car after car coming away from the demonstration, and it was exhilarating,” she said. “There was a sense of camaraderie; we were all in this together.”

Both women remember the sense of fear they felt after the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania in March of that year. It was that accident, Ms. Bredes said, that brought the risks of nuclear power to the forefront for many people and helped to fuel momentum for the demonstration.

After the protest, there were a number of meetings held in the community as people looked for the next step in the fight to make sure the plant didn’t operate, she said.

The rally marked a turning point in the attitude toward the plant within the local community that made that effort possible.

“This event was a kind of catalyst,” said longtime Wading River Civic Association president Sid Bail. “It divided this community.” In both Shoreham and Wading River, he said, a bulk of the people supported opening the plant, not only because of the tax benefit, but also because many of the residents were employed at Brookhaven National Lab and Northrop Grumman and were “comfortable” with the concept of nuclear energy. The plant also provided a lot of jobs, Ms. Bredes said, and the influence of the labor unions whose members worked on the plant was strong. Local politicians were also on board.

“Up until then, elected officials were hell-bent on supporting the tax revenues Shoreham was destined to provide to the school district, town and county,” said Greg Blass, who was a young lawyer at the time, newly settled in Jamesport, where a second power plant was being considered. They, along with champions of nuclear energy in Washington, D.C., he added, were so focused on the project, they took the community reaction for granted.

Opposition to the plant had existed within the community prior to the protest, Mr. Blass said, but hadn’t found the right outlet.

“When given the chance, the public opposition was profound,” he said. That year, he ran a protest candidacy against the nuclear plants for the first district in the Suffolk County Legislature and won. He said he was surprised. At the same time in Riverhead, residents voted the Jamesport plant down and ousted the town supervisor, who was in favor of the plant. “The sentiment had few opportunities of expression, unless it was the demonstration or a ballot proposition.

“It was the first time that the rumblings and unease about nuclear power plants came out,” he said. “But it was there, and for a good reason.”

Gradually, Ms. Bredes recalled, the political attitude on nuclear power began to change.

In his first meeting with the County Legislature, Mr. Blass said he sponsored a bill to get the legislature on the record in opposition to the Shoreham plant. It was the beginning, he said, because up until then they hadn’t taken a public position and had been very “kind and accommodating” with LILCO lobbyists.

But once the opposition had been voiced, local politicians began to change their positions, he said, starting down a path that ultimately led to the disapproval of the evacuation plan by the County Legislature in 1983 and, in 1989, the decommissioning of the plant and the formation of the Long Island Power Authority.

But not everyone was on board. Bill Carney, who had served as a county legislator and was elected congressman in 1978, was fully supportive of the Shoreham plant — and still is to this day. “I was for the plant opening, if it was safe,” he said. And though opponents argued the plant wasn’t safe or the evacuation plan wasn’t realistic, Mr. Carney said they were.

“I thought it was a bogus argument,” he said. “It was part of the technique of frightening people.”

The plant’s closure had nothing to do with its safety or the evacuation plans, Mr. Carney said, but a political agenda. Because Suffolk County and New York State had put additional safety requirements on the plant as it was being built — which also led to increased costs — the plant was the safest in the entire United States, he said.

Mr. Carney was congressman for eight years, and now owns a consulting firm that lobbies for the nuclear energy industry.

He left office, he said, because he wanted the plant to open, and people didn’t. “I guess I didn’t reflect their views,” he said.

“The Shoreham plant should have been opened and it hasn’t been,” he said. “We lost a lot of money and we lost a good, clean production of energy sorely needed for eastern Long Island.” Instead, he said, Long Islanders have been paying the bill for the state’s purchase of the plant and creation of LIPA, which he called a “terrible mistake.”

Mr. Carney wasn’t impressed by the June 3 protest, he said.

“I thought it was a waste, and I think it still is,” he said.

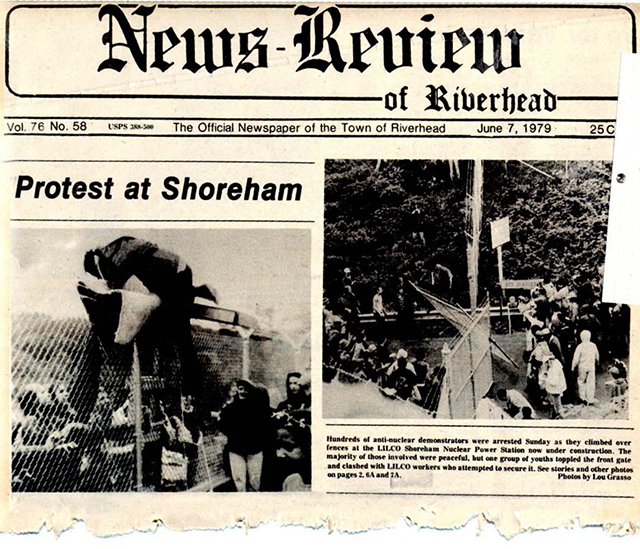

Top photo caption: Protestors demonstrating against the Shoreham nuclear power plant on June 3, 1979. It was the largest demonstration in Long Island history, and more than 500 people were arrested by the time it was over. (Credit: Courtesy/Peter Parpan)