A Times Review editor tackles ‘Troubles’ in novel, now in paperback

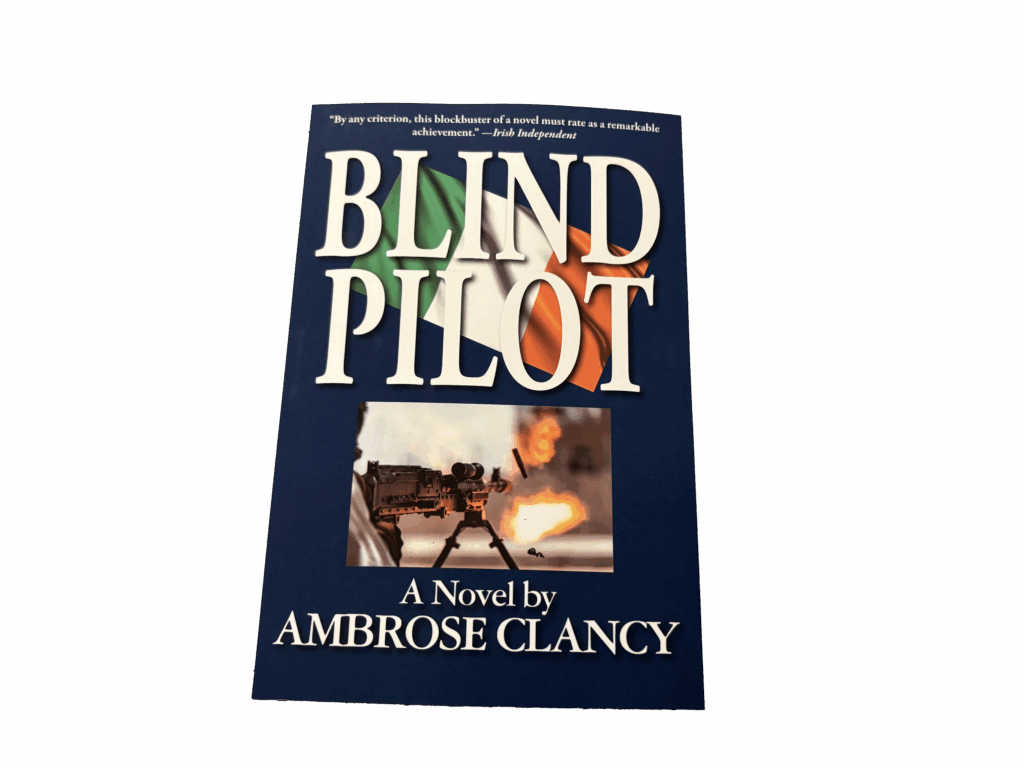

When “Blind Pilot,” Ambrose Clancy’s fast-paced and thrilling story of the Irish Troubles, was published in 1980, the newest chapter of the age-old conflict had been raging for a decade and would go on for another 20 years.

He held out little hope for peace in a country he had come to love while writing the intense and fictionalized account based on some true events. Now out in a new paperback edition from Brick Tower Press, its vivid cast of characters are drawn and dragged yet again into the Troubles that tore Ireland apart in the 20th century.

Although peace came to Ireland with the Good Friday Accord of 1998, the themes are relevant today, and rhyme with the violent political conflicts that still shadow human society.

The Baltimore Sun said Mr. Clancy’s feat is “to stare squarely at the darkest human impulse and the illusions that sustain it and document with almost a draftsman’s precision … One would have to look to the best novels of John le Carré and Graham Greene to find works that can be read with such pleasure as thrillers and such resonation as literature.”

The Washington Post reviewed the novel: “Clancy takes us up and back in time, into the past of his characters … Through it all, we see the reaching beauty of the country, feel its winds, hear its sounds, smell its pubs. And through it all, too, the war and its agents are moving.” The New York Times reviewer wrote: “A chillingly, well-informed thriller about Irish terrorism … A series of gripping and vividly narrated events … Striking pieces of imaginative writing.”

And Irish publications were also impressed. From the Irish Independent: “By any criterion, this blockbuster of a novel must rate as a remarkable achievement.” And the Belfast News Letter: “Ambrose Clancy knows his Ireland, its geography, its good people and its bad people … The authenticity is uncanny.”

Mr. Clancy is a journalist, known by Shelter Islanders as the editor of the Reporter for more than a decade. He also recently worked as interim editor of The Suffolk Times and Riverhead News-Review. In addition to “Blind Pilot,” he’s the author of “The Night Line: A Memoir of Work” and “My Life in Pieces: Writers, Rogues, The Road and The Rock.”

Although “Blind Pilot” is fiction, Mr. Clancy’s experience living in Ireland with his wife, Mary Lydon, during the Troubles was not. Working as a freelance journalist for The Village Voice, he spent time in the North of Ireland in the late 1970s, getting to know the war and the people who waged it from an uncomfortably close perspective. In those days, 14,000 British combat troops were on the ground in six counties of Ulster, and a guerrilla war was ongoing, with Irish Republican paramilitaries fighting to end British rule and Loyalist paramilitaries (in favor of continued British rule) fighting the Republicans. Added to the poisonous recipe were internecine battles within the groups.

“Belfast, especially in those days, could be a frightening and harrowing place,” Mr. Clancy said.

During their time in Ireland, Mr. Clancy and his wife traveled in the North, and once stayed in a small hotel in a beautiful little seaside town. They checked out and drove down to Belfast for lunch. There they overheard someone in a pub saying the name of their hotel and learned that it had been blown up just after they left. Mr. Clancy came to recognize the signature of a car bomb detonating a few blocks away, “the sound, the waves hitting you, the sidewalk kind of moving and shivering underneath you.”

His time observing the Troubles helped him understand the despair that settles in during a prolonged war. “We were living in Ireland in August of ᾽79 when Lord Mountbatten was assassinated. His boat was blown up, and three other people on board were killed. It was a horrible shock, and a lot of people thought, ‘What is the point?’ ”

Mr. Clancy goes deep into his characters, who are mostly based on people he met. He based one of his characters, Liam Cleary, on a man he met briefly, who had been in the Irish Republican Army since his teens and was assassinated while Mr. Clancy and his wife were living in Dublin. “The assassination of a charismatic leader. The real shock about it. And real sorrow, that struck me,” he said.

There are characters to fall in love with, and laugh with, and some to pity, before Mr. Clancy gets to the tragic end of his story.

“It was my intention to focus on the people, and not just as instruments to keep a plot rolling, but their past, their interior lives.” He added, “There are people in the book who are major characters that I met in an afternoon, and they were just so striking. People you’d run into as a journalist that you just don’t forget.”

That intense involvement in the lives of his characters took a toll on him during the writing, and his wife eventually told him so: “Mary said, ‘It was strange to live with you. You were killing all those people, and we would be together, and you would be somewhere, away, and very upset.’ Novel writing — it’s a spooky art, as someone once said.”

In his acknowledgments, Mr. Clancy thanked the people of Ireland. “It was kind of grand and maybe stupid. Why? Well, because there are some people in Ireland who you wouldn’t want to sit next to on a bus. But that doesn’t mean they weren’t part of my story. I wanted to express my gratitude for all the people that I ran into. For their sense of hospitality, their sense of caring, for welcoming the stranger. All that was part of the book.”